I hold no illusions that having an opportunity to meet my favorite heroes in sports or popular music would be highly stimulating, much less edifying. As a result, I immediately turn off the TV before the winning and losing athletes are interviewed, or head for a restroom break at concerts when the vocalist decides to enrapture his/her captive audience with political erudition. I’m no longer stunned that athletic or musical brilliance is often unaccompanied by an ability to string cogent thoughts together in a conversational setting.

I hold no illusions that having an opportunity to meet my favorite heroes in sports or popular music would be highly stimulating, much less edifying. As a result, I immediately turn off the TV before the winning and losing athletes are interviewed, or head for a restroom break at concerts when the vocalist decides to enrapture his/her captive audience with political erudition. I’m no longer stunned that athletic or musical brilliance is often unaccompanied by an ability to string cogent thoughts together in a conversational setting.

There are exceptions, of course, and one hope that I harbor is a chance to meet two musicians, engaging and intelligent both in and out of the recording studio – Brian Eno and Robert Fripp. As long as I’m dreaming, I’d like to meet them over a long Sunday lunch, outdoors, at a small restaurant in the Vaucluse region of France. Stuffed lamb shoulder, green beans, warm fresh bread, and strong French coffee. I digress.

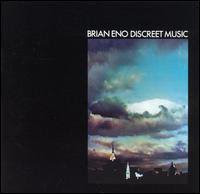

Brian Eno began his rock career on the first Roxy Music album (1972, credited simply under the name Eno). He then left the band and continued his experimentation in tape looping, ultimately becoming the father of ambient music. If your favorite band suddenly acquired a sound that added richness and complexity that didn’t exist on their previous albums, there’s a fair chance that Brian Eno was brought in to produce the album. A very short list of artists to enjoy Eno’s production and engineering attentions are Talking Heads, U2, David Bowie, and Coldplay.

Robert Fripp is a founding member of King Crimson, a band in the top echelon of experimental and progressive rock. Not satisfied with that, Fripp has launched any number of side projects that include everything from classical guitar to Frippertronics, an electric form of guitar and recording treatments he invented. A host of acclaimed rock’s elite have made their way through King Crimson as well, including Greg Lake, Adrian Belew, Jon Anderson, John Wetton and Tony Levin.

What is truly fascinating about these two is that they are as intelligent off-stage as on, as shown in the many published interviews and writings of both musicians. Robert Fripp has a personal website that is the most interesting and informative of any rock artist I’ve tripped across – dgmlive.com. I’ve no doubt a lunch al fresco with these two gentlemen would be the experience of a lifetime.

Occasionally , these two will team up together on an album, the results of which are always exciting. They have done this four times, always instrumental, and the combination of Eno’s ambient loops and Fripp’s mesmerizing guitar treatments make for sublime listening. I suggest Evening Star (1975) as a starter. Also, each have a new work released, which I highly recommend: Brian Eno – Lux, and A King Crimson Projekct – A Scarcity of Miracles.